4x5 RB Auto Graflex

A large format single lens reflex (SLR) camera

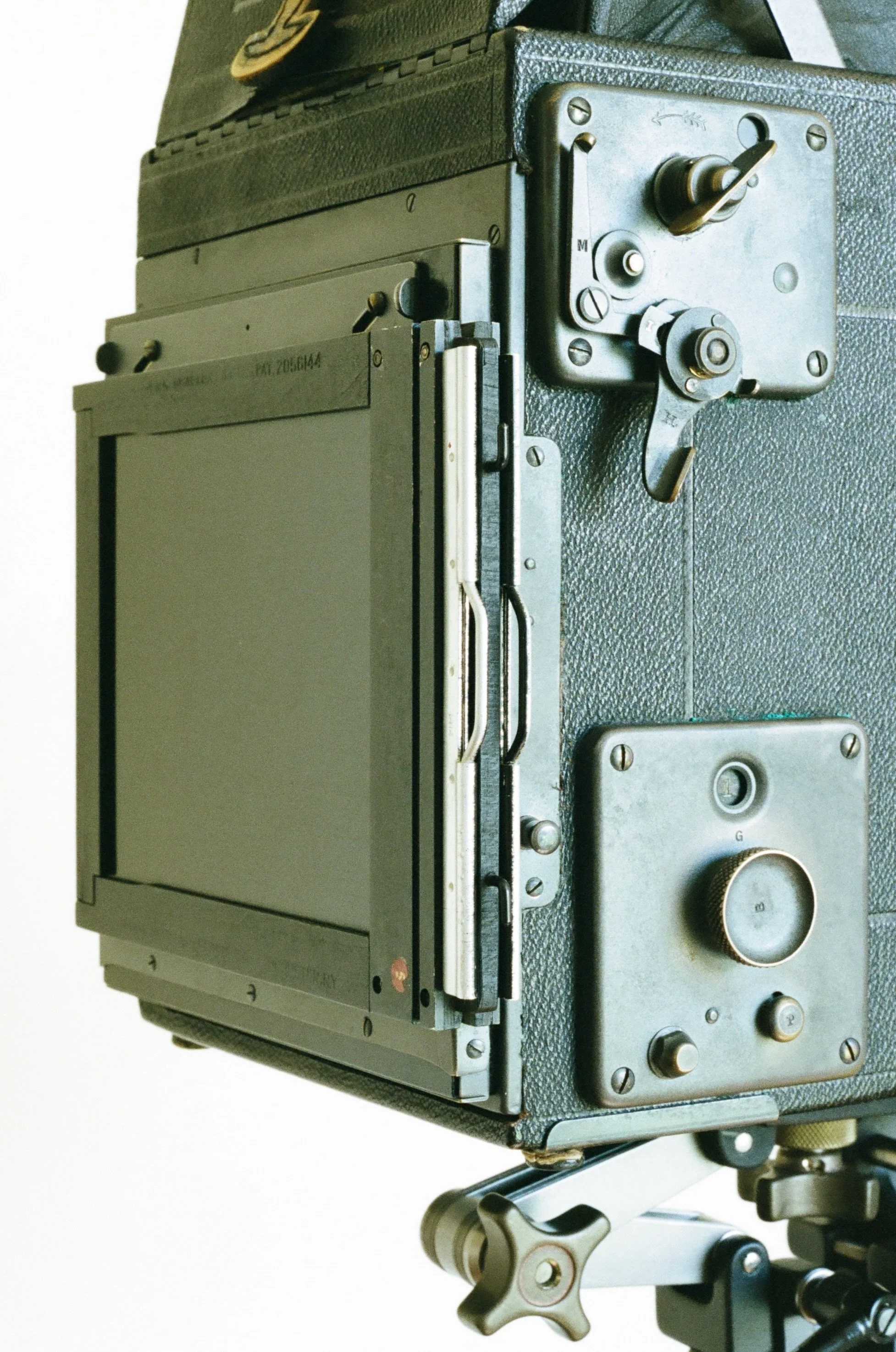

4x5 RB Auto Graflex. Here, it’s on a tripod but I use it hand held. (Color photos of the camera were made with a Nikon F, 55mm f/3.5 Micro-Nikkor-P.C, and Portra 400.)

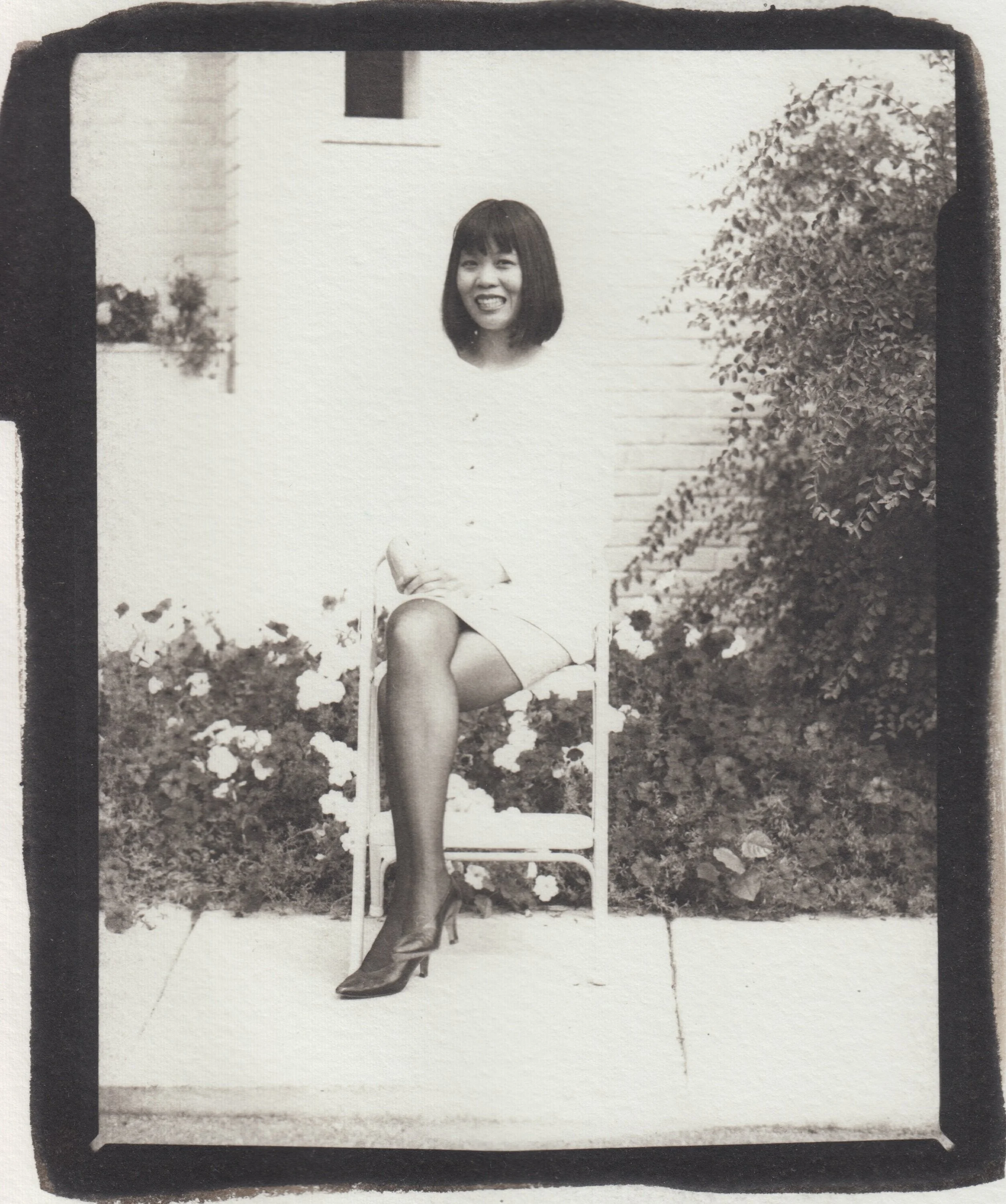

Roppongi, Tokyo. Negative: 4x5 RB Auto Graflex, 25cm f/4.5 Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar, Tri-X, early 2000s. Print: Platinum-palladium from the original camera negative, 2025.

100 years ago, most SLRs were large fomat cameras

‘In 1902 the patents for the first Graflex single-lens reflex camera were issued’ and Graflexes remained in regular use through the mid-20th century (Holden, 1958). The 4x5 RB Auto Graflex was made from 1906 to 1941. The last Graflex in production was the 3 1/4 x 4 1/4 RB Super D, made from 1941 to 1963 (McKeown’s, 1996).

Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, Tina Modotti, Edward Weston and Alfred Stieglitz made extensive use of Graflex cameras. Pritchard (2015) credits Stieglitz’s most famous photograph, The Steerage, to the Auto Graflex. Weston described his and Modotti’s use of a Graflex in his Daybooks and he photographed Modotti holding a Graflex in Mexico in 1924 (Argenteri, 2003). In 1923 Weston wrote:

‘The Graflex is a spontaneous camera but lacks the precision of a view box planted firmly on a tripod… But I say this at the same time defying most anyone to say which are my prints from direct 8x10 negatives and which are those from enlarged negatives’ (Daybooks, Mexico, p. 84).

4x5 RB Auto Graflex with its 25cm f/4.5 Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar lens.

Graflex v. Speed Graphic

Today, the Speed Graphic is sometimes referred to as a ‘Graflex’. That was not the contemporary usage. The two cameras were made by the same company at the same time, but they were very different product lines. Like BMW and Mini Cooper.

Both cameras were designed for hand held use, were made in multiple formats, and had a leather-covered wooden structure, but the similarity ends there.

The Graflex is a single lens reflex (SLR) with a waist level finder. In the nomenclature of 20th century camera design, ‘flex’ denotes a reflex camera. That is, one with a mirror to reflect the image from the lens onto a viewing screen for composing and focusing the picture. Because the Graflex is an SLR, composition and focusing are precise except in low light, when the image becomes dim.

The SLR design has limitations:

Complexity, bulk, and weight.

There is a minimum focal length required, so that the lens does not interfere with the mirror.

The camera angle is low because the photographer is looking down from above, through a tall focusing hood.

Also, Graflex cameras are incompatible with standard film holders. They use dedicated Graflex film holders that are flat, with slots along the edges. They attach to the camera with a slide lock as shown below.

The Speed Graphic is fundamentally different. It’s a rangefinder camera. Composition is done at eye level. It uses standard film holders, and is much smaller and handier than a Graflex. A shorter focal length lens is commonly used; mine is 127mm. I carry my 4x5 Speed Graphic under the seat on airplanes; not feasible with the 4x5 Graflex. On the other hand, composition and focusing with the Speed Graphic is more approximate.

Both cameras can be used as tripod-mounted view cameras but they are not the best choice for that; their designs were optimized for hand-held use.

The Graflex film holder is attached to the camera back with a slide lock (there’s no spring back).

Two 4x5 film holders both made by Graflex Inc. Left: Graflex film holder with slotted edges, for Graflex SLR cameras. Right: Standard film holder for the Speed Graphic and other 4x5 cameras.

Top: Graflex 4x5 film holder. Bottom: standard 4x5 film holder.

The manufacturer was repeatedly bought and sold

The Graflex and the Speed Graphic were originally products of the Folmer & Schwing Manufacturing Co. which began camera production in 1897. The company was purchased by George Eastman in 1905, then it was ‘dissolved In 1907, becoming first the Folmer & Schwing Division of Eastman Kodak and then in 1917 the Folmer & Schwing Department of Eastman Kodak Co.’ Kodak spun it off in 1926 as the Folmer Graflex Corporation.

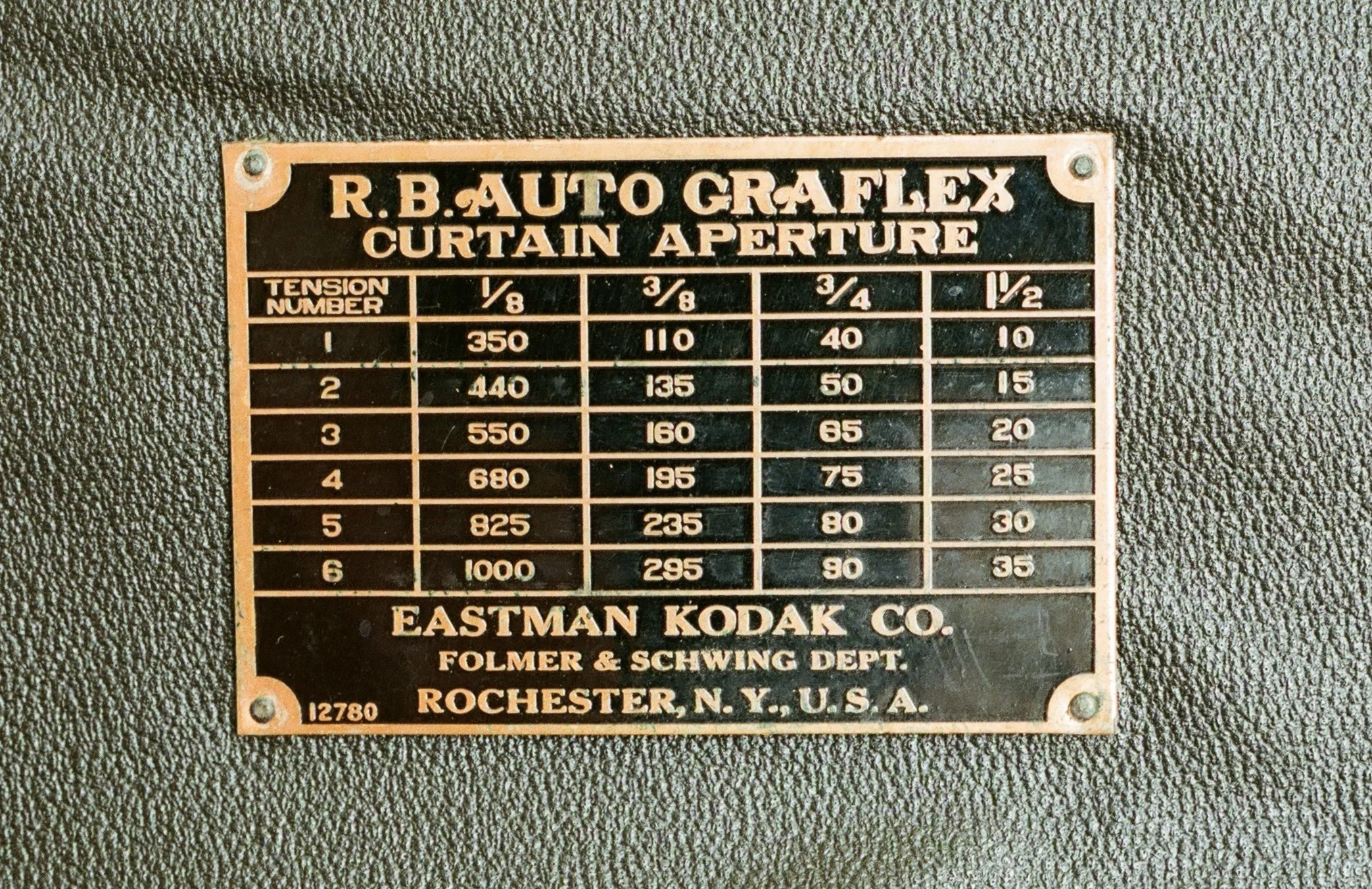

My camera’s nameplate is marked Folmer & Schwing Dept., indicating it was made between 1917 and 1926.

In 1945 Folmer Graflex Corp. renamed itself as Graflex, Inc. Then in 1956 Graflex, Inc. was acquired by General Precision Equipment Corporation which in 1968 was acquired by Singer Corporation (famous for sewing machines). Singer dissolved Graflex in 1973.

(Source, including quotes: McKeown’s, 1996.)

Portrait photography Behesda, Md. Negative: 4x5 RB Auto Graflex, 25cm f/4.5 Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar, Tri-X, late 1990s. Print: Platinum-palladium from original camera negative, 2025.

Using the Graflex

Graflexes are heavy and bulky but they have good hand-held ergonomics. Making an exposure is a multi-step process due to the simplicity of the mechanism. See the appendix for more about the shutter.

A definite weak point, is that the Auto Graflex has a manual aperture mechanism, as with a rangefinder camera or view camera. For the latter two camera designs, the manual aperture is not an issue because the photographer is not looking through the lens when the picture is made. On SLRs though, the manual aperture slows things down a lot:

First, the lens is set wide open (f/4.5) for good visibility. The picture is composed and the camera is focused.

Then you bring the camera down to set the aperture for the exposure (for example, f/8 or f/22).

Then back up to the eye take the picture.

Alternatively, for faster action, composition and focus can be done with the aperture set for the exposure. That works fine when the exposure calls for a large aperture. But when stopped down, the image is dim. Edward Weston used a Graflex and he wrote of the difficulty in focusing and composing with the lens at f/32 (Daybooks I: Mexico [Weston 1990], p. 84).

The manual aperture was a general weakness of early SLR cameras. The solution was the automatic aperture, in which the aperture is pre-set for the exposure while remaining wide open for composition and focusing, then it stops down automatically when the shutter is tripped.

The first Graflex with an auto aperture was the 3 1/4 x 4 1/4 RB Super D model, which began production in 1941 (Morgan, 1958:210). This was an important innovation, highlighted in the camera manual. For decades after, many SLR lenses were marked ‘Auto’ to emphasize this feature. See the Nikon F and the Mamiya/Sekor 1000 DTL for examples.

Maintenance and repair

The shutter mechanism was overhauled and the curtain was replaced in the late 1990s by Penn Camera Exchange, a Washington, D.C. camera shop that is no longer in business.

References / further reading:

Instruction Manual for Graflex Cameras: RB Super D, RB Series B, and Earlier Models Including Series B, RB Series D, Auto, RB Auto, Auto Jr., RB Tele, RB Jr. Rochester, N.Y.: Graflex, Inc., n.d.

Available from orphancameras.com at: https://www.cameramanuals.org/prof_pdf/graflex_cameras.pdf

Page 4 has a description of the shutter mechanism, and how the desired shutter speed is set by selecting a combination of curtain aperture and tension.

More references:

Argenteri, L. 2003. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale University Press.

One of the full-page plates following p. 142 is a photograph of Tina Modotti and Miguel Covarrubias taken c. 1924 by Edward Weston. Modotti holds a Graflex. My guess is that it is the 3 1/4 x 4 1/4 that Weston describes in a 1924 entry in his Daybooks I: Mexico (Weston 1990, p. 84).

Gustavson, T. 2011. 500 Cameras: 170 Years of Photographic Innovation. New York: Fall River Press.

The 500 cameras are from the George Eastman House Technology Collection, Rochester, N.Y. The 4x5 RB Auto Graflex is on p. 158. It is described as made ca. 1910, owned by Alfred Steiglitz, and donated by Georgia O’Keefe.

Holden, T. T. 1958. Graphic & Graflex Equipment. Chapter 17 in W.D. Morgan, Graphic and Graflex Photography, 11th ed. New York: Morgan & Morgan.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017759800/ accessed Sept. 28, 2025.

A 1936 photo of Dorothea Lange sitting on top of a Ford, holding a large format Graflex. Title of photo: ‘Dorothea Lange, Resettlement Administration photographer, in California’. This photo is mentioned in Pritchard, 2015 (p. 73).

Matanle, I. 1996. Collecting and Using Classic SLRs. New York: Thames and Hudson.

pp. 9-14: The early history of the SLR is here, including the Graflex and SLRs from British and German companies. The Zeiss Miroflex, a folding SLR, is pictured.

pp. 241-255: Chapter 12, ‘Using the really old ones’, offers advice on using early SLRs.

McKeown, J.M. and J.C. 1996. McKeown’s Price Guide to Antique and Classic Cameras, 1997-1998. Grantsburg, Wis.: Centennial Photo. Graflex is on pp. 222-228.

Morgan, W.D. 1958. Graphic Graflex Photography, 11th ed. New York: Morgan & Morgan.

Pritchard, M. 2015. A History of Photography in 50 Cameras. Buffalo, N.Y.: Firefly Books.

pp. 70-71: ‘The first true SLR camera was invented by the English photographer Thomas Sutton and patented by him in 1861… During the 1890s, new designs were produced by a number of manufacturers. Of these, the Graflex reflex camera, launched in 1898, was the most long-lived and influential in terms of defining the general design of reflex cameras’.

p. 73: the Graflex is discussed and it is mentioned that Alfred Stieglitz’s 1907 photograph The Steerage was made with an Auto Graflex.

Taylor, Alan. 2019. ‘The Photography of Margaret Bourke-White’. The Atlantic, Aug. 28th.

Sotheby’s Auction, New York, 2020. Photographs from the Ginny Williams Collection. https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2020/the-ginny-williams-collection-photographs-online?lotFilter=AllLots

Lot 65 is a famous scene; a photograph by Oscar Graubner (1897-1977), c. 1930, ‘Margaret Bourke-White atop the Chrysler Building’. Lot 8, another photo by Graubner of Bourke-White, more clearly shows the camera.

Weston, Edward (Nancy Newhall, ed.) 1990. The Daybooks of Edward Weston: Two Volumes in One. I. Mexico, II. California. New York: Aperture.

This is an essential source on photography in the 1920s and 1930s, from both the artistic and technical perspectives.

Wilson, C. 1998. Through Another Lens: My Years with Edward Weston. New York: North Point Press (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux). Plate 28 is a 1935 self-portrait of Weston with a Graflex, it looks like an RB Auto model.

Appendix: The shutter

The Graflex’s focal plane shutter is a single strip of cloth (a ‘curtain’) with a series of slits (‘curtain apertures’) of different widths. The film is exposed when the selected slit moves from the roller at the top to the one on the bottom. Shutter speed is then a function of two variables: (1) the width of the slit (curtain aperture), and (2) the speed at which it travels across the film plane. The latter is a function of spring tension.

A table on the camera’s name plate states the available shutter speeds in terms of combinations of the two variables: shutter slit (‘curtain aperture’) and spring tension. Find the shutter speed you want, set the corresponding curtain aperture and tension number, and you’re ready.

When rewinding the shutter, the curtain aperture travels back across the film plane. To avoid a re-exposure, keep the dark slide in place at all times except at the moment of tripping the shutter.

Shutter settings chart on the camera nameplate.